Asset and productive economies

Hector McNeill1

SEEL

There is widespread reference to asset, real and, to a lesser extent, productive economies. However, the relationships between them are quite often not made very clear. The economic interests of different people are associated with these types of activities to varying extents. Therefore an understanding of the distinctions and the determinants of beneficial operations is important for policy design.

The asset economy

Assets are objects or undertakings governed by contracts that have an economic value in that they can be sold in exchange for money or swapped for other assets. Usually an asset is used as a store of value or as something that provides an income stream. However, the asset economy which is based on transactions involving assets either as the exchanged items or as the stores of value used to reduce the risk of some form of financial exposure. In fact the asset economy tends to be concentrated and involving a small percentage of the population who have the levels of financial resources sufficient to trade in assets or who use assets of others to underwrite financial asset transactions. Thus the purchase of rare art and the use of a borrower’s house as a guarantee for a mortgage are typical transactions in the asset economy. Financial derivatives are also assets that provide income streams but these often rely on a tiered legal structure where those who provide the income stream are not party to the exchange of derivatives.Assets & derivatives

Although banks and companies might hold portfolios of assets and derivatives they are different in terms of their sensitivity to policy. Assets are usually objects whose main value is their role as a store of value with their intrinsic value being their potential sales price.

Derivatives are "financial products" made up of time-based transactions. Time-based transactions involve the transfer of money from one party to another in an agreement whereby a person or company undertake to pay another party sums of money at regular intervals. This could be the repayment of a loan. The loan may be guaranteed by some asset. Thus in the case of a mortgage payment the guarantee is the house being financed or purchased under the mortgage concerned. The differences in sensitivity to policy is that the ability of the party to continue to payments is an important "fundamental" whereas the asset function as a guarantee takes up the role of normal assets (store of value and sales price).

There is some confusion associated with the forceful assertion by some that derivatives are "products" on par with output in the productive economy, created as a result of the transformation of combinations of financial contracts (inputs) into derivatives (output). |

|

|

Thus a derivative can be the income stream generated by a collection of mortgage contracts while the income stream provided by the derivative is the sum of the amounts paid by the mortgagees each month and "rolled up" in the derivative.

A major concern in the asset economy is that asset prices are maintained or increase. There is a preference on the part of asset holders for at least price stability or a slight increase so as to counter inflation whereas there is no desire for asset holders to see assets facing price declines, or a deflationary situation. In periods of scarcity of specific products purchased as an asset (such a coffee futures or precious metals) asset prices can rise significantly. Today, the volumes of funds held by financial intermediaries can be used to manipulate commodity and financial markets including having control over the speed of delivery of physical commodities so as to gain an ability to increase margins from imposed price rises. This form of transactions sometimes based on high frequency trading is confused with speculation which entails more risk.

The productive economy

The majority of the population is employed and conduct their economic activities in pursuits that contribute to the productive economy. The productive economy is typically made up of economic units that purchase inputs and transform these into outputs in the form of goods and services. People earn income from their employment as contributors to the activities of the economic unit. Owners and shareholders gain from dividends, salaries as well as maintaining the right to participation in the current and future proceeds and growth of the activities of the economic unit. In contrast to the asset economy the major concern is to earn margins on productive activities that make use of purchased inputs that are transformed. There is therefore an interest in identifying and purchasing the lowest priced inputs that satisfy the required properties for the transformation processes used. The judgement of the relative attractiveness of an input price is related to the significance of that particular input amongst all others, contributing to the aggregate unit costs of units of output and the view of the relationship of feasible unit output prices to that aggregate unit input cost. In the context of the profit motive, there is therefore a natural interest in the factor or input markets being characterized by unchanging or even falling unit prices (deflation) whereas in term of profits there is a preference seeking higher unit prices resulting in a upward pressure on prices (inflation).

Policy implications

There is a constant reference, in the context of policy making discussions, to the need to avoid deflation. However, the specific prices being referred to are seldom specified. In the discussion so far it has become evident that deflation of production input prices is of direct benefit to an economic unit in the productive economy so as to be able to access lower prices and therefore costs for their activities. On the other hand those holding onto assets as a store of value don’t want deflation but in fact have a preference for inflation in asset prices.

This sums up the challenge facing policy design. To what degree do current policies balance these distinct and different preferences of the asset and productive economies?

Inflation, interest rates & purchasing power

Interest rates compound inflation by increasing the price of transactions that involve finance. This fact is often not clear because of the fact that interest rates are an instrument used to squeeze inflation out of markets by raising interest rates so as to reduce purchasing power and therefore “demand”. However, the fact that this eventually can lower inflation should not detract from the realization that interest rates have an inflationary impact on both inputs and outputs of the productive economy that are financed when interest rates are raised. As companies face falling demand they end up with under-capacity operations leading to higher operational costs. The duration of this process depends upon the traction achieved and time taken to secure lower inflation. This, indeed, is how interest rates impact productive activity as well as consumption.

The recent (2007) widespread failure in the performance of asset portfolios dominated by derivatives (based on sub-prime mortgages for example) was due to a fall in the price of those derivatives. This decline was caused by interest rates being raised by a quite small amount by the Federal Reserve in November 2007 from a very low level. So a 1% increase from 2% is equivalent to a 50% rise in premiums. Because the nominal incomes of those paying mortgages did not rise and their total outgoings where close to their maximum disposable incomes so their purchasing power, or capacity to pay premiums, declined. Most mortgage payers earned their income from the productive economy, which was also negatively impacted by higher interest rates. In an attempt to reduce overheads on lower output many lost their employment resulting in absolute declines in income. This had a knock on effect of house repossessions and an overall decline in the value of houses as an asset. As a result both the income stream and the asset values within the derivative concerned converted them into lower value assets or “junk”.

The current state of affairs with low interest rates and quantitative easing faces this risk, yet again, when interest rates are raised or "tapering" begins.

The impact of interest rise of 1% from low base

| base | increment | increment as

% of base |

| 1 | 1 | 100% |

| 2 | 1 | 50% |

| 3 | 1 | 33% |

| 4 | 1 | 25% |

| 5 | 1 | 20% |

| 6 | 1 | 16.7% |

| 7 | 1 | 14.3% |

| 8 | 1 | 12.5% |

| 9 | 1 | 11.1% |

| 10 | 1 | 10% |

|  The relative impacts of interest rate changes

For each rise of 1% rise in interest rate there is a corresponding estimate of the percentage rise in the price of money (rental).

Thus a rise in interest rate from 2% to 3% represents a rise in interest rate of 100(3-2)/2 = 50%. A rise in interest rate from 5% to 6% represents a rise in the interest rate of 100(6-5)/6 = 16.66%.

The graphs shows that the lower the interest rate regime the higher the relative impact on standing loans and financial agreements, such as mortgages, of rises in rates. |

|

|

Inflation

The world's central banks, including the Bank of England, consider "price stability" to be an essential policy objective. In general, in order to avoid risking deflation of asset prices this policy sets an annual inflation rate of around 2% to represent a policy target as being an acceptable indicator of price stability. On the other hand this stabilizes the underlying guarantees for financial transactions in the form of assets held as a portfolio of guarantees against loans, or as derivatives generating an income stream. The behaviour of asset markets is generally that prices tend to accompany inflation so asset holders including those using assets as financial guarantees (such as financial intermediaries, banks etc) do not suffer falls in the real values of these assets whereas they earn margins over and above the assets values in the form of service fees and margins built into interest rates charged for those borrowing money.

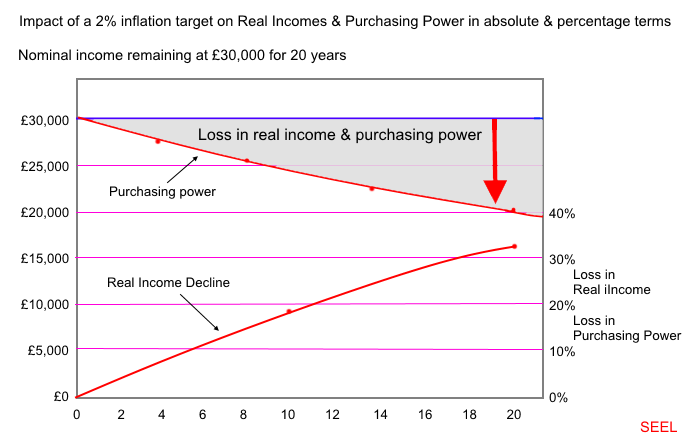

However, a 2% annual inflation rate reduces the purchasing power of wages by 18.30% within just 10 years. As a result, monetary policy causes a constant depreciation in real incomes. The table below shows the decline in purchasing power under a 2% inflation rate over a 20 year period of a nominal income of £30,000/year. A 2% inflation is almost a 20% devaluation of real incomes and/or an increase in input values of 20% each decade. This clearly compromises the operation of the productive economy in terms of the unit prices of inputs and the level of wage payments in that government revenue-seeking through taxation of corporate profits provides a disincentive for raising wages in line with inflation. As a result there is a trade-off between asset values or asset-based service profits and real wages and input costs. Thus policy creates a situation hat is equivalent to a hidden subsidy paid by companies and wage earners in the productive economy to the financial intermediation activities and other participants in the asset economy. Thus the asset economy appears to grow at the expense of the productive economy.

| Year | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 |

| Nominal Income | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 | £30,000 |

| Real Income | £30,000 | £28,812 | £27,671 | £26,575 | £25,522 | £24,512 | £23,541 | £22,609 | £21,714 | £20,854 | £20,028 |

Fall in real incomes | Fall in real income due to policy of target 2% inflation is 18.30% after 10 years and 33.24% after 20 years

|

This set of relationships is presented in the graph below.  Purchasing power and real incomes Purchasing power and real incomes

As one can observe, policy based upon the monetary instrument of interest rates has a pervasive negative effect on the purchasing power of the incomes which in aggregate make up the national income. A fall in purchasing power is the same as a decline in real incomes of:

- Home owners (wage earners)

- Financial intermediaries

- Production units

- Government

Who should care?If one compares the particular concerns of constituents with this reality of interest rate-based monetary policy it is evident that those who benefit are those who rely more on asset values and this is a small percentage of the social constituency who are engaged in economic activities that rely on asset values as a basis for sustainability and levels of profit. Clearly this segment are those who own economic units or are employed in financial intermediation. Even if interest rate policies are eroding the purchasing power of the currency, as long as nominal income increases outstrip the 2% inflation, then these constituents will not be affected by a fall in real incomes. Those affected more directly by such policy are economic units in the productive economy and those employed in the relevant sectors. There is therefore a clear conflict of interests within the social and economic constituencies that is imposed by policy and this is a matter of serious concern because policy should not be biased towards a specific section of the constituency but should be impartial, that is, it should, at least, aim to establish a "level playing field". The breakdown between "winners" and "losers" based upon available statistics is that some 20% of the social constituency gain benefits from having all or some of their economic activities or employment being related to the asset economy and the 80% of the social constituency who remain in balance (around 15%) while the remaining 65% are essentially "losers". This matter is one of serious constitutional concern and policy makers need to review the theoretical and practical implications of conventional policy in the context of its failure to accommodate the needs of the whole constituency complex. This is not a simple problem; it is complex. Certainly conventional macroeconomic theory, practice and the existing policy instrument toolkit cannot influence the determinants necessary to correct this perversity because theory and practice have not recognized this as a policy-derived problem and therefore have not identified the specific policy target, the determinants of that target and the appropriate policy instrument to achieve that target which has an effective and efficient traction. The Real Incomes Approach to economics has identified the principal target as real incomes, the prime determinant at the level of the firm to be the Price Performance Ratio (see "The price performance ratio")and the required instrument to be Price Performance Levy (see "The price performance levy"). A successful implementation of such policies relies upon the foundation of the Production, Accessibility & Consumption Model of the economy (see "The PAC Model of the Economy") and the real growth multiplier (see "The Real Growth Multiplier").

1 Hector McNeill is the director of SEEL-SystemsEngineering Economics Lab. All content on this site is subject to Copyright

All copyright is held by © Hector Wetherell McNeill (1975-2015) unless otherwise indicated

|

|

|

|