Hector McNeill1

SEEL

Unless it is possible to test an economic theory by demonstrating a working model of how it might work in practice, the stated objectives, policy instruments and expected outcomes will remain uncertain.

This paper is an introduction to an online simlation series concerning real incomes policy. However, the discussion will concentrate on one or two scenarios to explain the significant factors that determine real income levels to demonstrate how policy can help stimulate sustained economic growth.

The simulations are designed to answer the following questions in a transparent manner:

- How does the real incomes policy incentive help encourage a positive response on the part of economic particpants in the real economy?

- What economic principles should companies and their workforces apply to maximise real incomes?

- What are likely comparative increases in productivity between:

3.1. the real incomes policy framework (RIPF)

3.2. the conventional economic policy framework (CEPF)

- What is the comparisons of risk associated with investments in a RIPF and CEPF?

- What are the comparative levels of policy traction between RIPF & CEPF?

- What are the comparative levels of real economic growth & real incomes?

|

The economic situation in the 1970s and 1980s, that gave rise to a greater focus on "supply side economics", is identical to the current situation of a largely stagnant world economy with policy-makers attempting to recover from the recent financial crisis. This similarity is not generally detected because economists concentrate on policy indicators such as inflation, interest rates and employment levels which in each situation appear to have moved in diametrically opposed directions. For example, sumpflation was a situation of a combined high inflaction and rising unemployment and the current recession is an association between low inflation and higher, lower income employment, so how can one situation be considered to be the same as the other? The

main single common factor in each case is

declining real income levels for the majority and there is also the associated

increasing skew in income distribution. Therefore, what we can determine is that the past inflationary slump (stagflation) is, in real income terms, the same as the current deflationary recession. This single priority factor has never been emphasised in exchanges between policy-makers and economists because real incomes is considered to be an indirect outcome of policy. This failure to prioritise real incomes arises from Fiscal, Monetarist and Keynesian approaches to macroeconomic management all applying the same Aggregate Demand Model (ADM). This model provides a "policy franmework" where only a limited number of instruments are used in an attempt to "stimulate" demand. The instruments include:

- the setting of interest rates

- altering tax rates on corporations or individuals

- raising government loans and expenditures where government revenues are insufficient

- fixing exchange rates

|

Beyond these instruments this conventional macroeconomic policy tool box is empty.

The desired trend in the economy is for disposable incomes to be able to purchase the same or increasing amounts of goods and services. Thus, the purchasing power of disposable incomes needs to remain stable or rise. The only way to achieve this is for:

- unit prices to fall

- the value of the currrency to remain stable or increase

- nominal incomes to rise

For unit prices to fall, there is a need for companies producing goods and services to increase their productivity in physical, economic and financial terms.

Macroeconomic policy, based on the ADM cannot achieve this effciently because the necessary changes can only be actioned by those who participate directly in economic processes including the self-employed, corporate owners, management, workforces and government services.

What emerged as "supply side economics" in the 1980s is essentially a fiscal policy based on the lowering of marginal corporate tax rates. In practice it proved to be able to secure some marginal real economic growth but policy traction declined because there were no direct incentives for decision-makers to "follow" the policy intent. This is because supply side economics is not supportd by any focussed motivational incentives to influence the decision-making of those involved in economic activities. To put is bluntly, if corporate tax is reduced, owners do not have to invest that money in productivity-enhancing investments when they can earn more, even in the short run, by investing the higher margins in assets that have nothing to do with the mainstream company activities or generating returns on those activities; owner incomes and managment bonuses have come increasingly from parallel acivities that are not reliant on mainline activity productivity.

As it is described and as it was applied,

supply side policy is unable to create a failsafe framwework whereby real incomes and productivity will increase in a predictable and desirable fashion; the degree of policy traction (delivery) remains uncertain.

On the other hand a real incomes policy which makes a direct use of supply side actions by making real incomes the core policy target to secure a economic growth by providing:

- A focus on the real economy:

- an incentive for those pursuing economic activities to increase the productivity of their mainstream activity

- Clear guidelines for policy response by economic and social constituents:

- a proactive mechanism whereby any participant attempting to increase productivity can excel in doing so

- Lowering risks:

- a mechanism for ensure that compensation for the traformation of productivity into consumers real incomes be secured within a short period by an equivalent increase in real incomes of those actively engaged in the production process

|

One major reason that supply side policy is inefficient is that the risk assessment of investment opportunities have changed significantly becoming less favourable to the real economy and more favourable to financial engineering. This has been a major cause of the rapid conventration of income and assets in the hands of a small group following the low interest rate regimes that came into play after 2007-2008 through quantitative easing. The time for an investment to come on stream and generate a return is usually longer in the real economy when compared with financial dealing. As a result, investment in productive activities is perceived to be of higher risk. This is a direct disincentive for the necessary investment in corporate activities to raise productivity. As a result conventional macroeconomic policy instruments cannot bring about the real incomes growth necessary to escape from the current economic circustances; conventional macreoeconomic policy increases risk. Therefore a significant aspect of any policy aiming to achieve real incomes growth is an ability to help companies outperform others who prefer to divert investment into financial dealing. In the end, companies will only collaborate with a real incomes policy if the owners and management recognise that it is less risky and more profitable for them.

Real incomes are the measure of the purchasing power of disposable incomes. Therefore real income levels as an objective of policy is a comprehensive indicator which integrates dynamic changes in several factors including:

- the working age population and the distribution of employment

- the relative productivity of activities and the relative compensation of those employed as nominal income

- the movement in unit prices, that is, inflation or deflation

- movement in exchange rates

The real incomes chain is made up of transitions or productive activities where the unit prices of inputs determine unit costs according to the volume of saleable output. The unit output price establishes the margin over unit costs and the total margin is the product of the values sold and unit prices charged.

The relationship between sustaining or increasing real incomes and productivity has been touched upon above. We will now come to the practical considerations facing managers and workforces when deciding on the pathways to higher productivity that will benefit the returns to the economic activity. The Smithonian concept of each pursuing their own specialisation being the catalyst for creating benefits for the whole of society will only work if there is a balanaced relationship between increases and physical productivity and unit prices and the resulting margins and volume of sales. Thus a process that raises productivity significantly and lowers unit costs might be marketed to a high income group, thereby limiting the general benefit but gaining significant margins and a high return. This is a trend that can be observed in high technology industries such as mobile telephones. The broader benefit has resulted not from the high end high-priced products but from lower-priced emulations where margins are lower but sales volumes are high. This serves to illsutrate the nature of the decisions required in managing the outcome of increasing productivity. The normal justification as to why new products are high priced is to recover investment costs. Indeed, any investment involves risk and management will tend to err on the side of attempting to maximise unit returns to ensure investment cossta re recovered as quickly as possible. Within the current conventional economic policy frameworks, investors are not provided with any practical support in lowering their risks if the pricing decisions involve price reduction, lower margins and the hope of higher sales. However, in terms of the general benefit to the economy and consumers, this is the desirable state of affairs which macroeconomic policy should attempt to encourage.

There is a significant misnomer in the current discourse of political exchanges and this is the confusion between the terms "incentive", "subsidy" and "government give-aways". An intelligent policy inventive should not be a subsidy and therefore does not have to involve any public funding. An incentive should represent a tranparent means of improving economic and financial performance,

in the context of this article and the Smithonian sense of benefit, an incentive should provide a means of increasing real incomes of producers as well as consumers.

Therefore policy instruments need to permit managers and workforces to manage their affairs to augment their real incomes in such as way that society as a whole also benefits. Therefor incentives need to support this process by reducing investment risk.

There is a direct trade-off between unit prices and margins in association with any given unit cost. The risk consideration is associated with the relationship between unit prices and likely volume sold since this will establish the size of the cash flow used to pay back investment.

During the last half century, at least, monetary policies have tended to target an inflation rate of 2%. This results ina policy-induced devaluation of the currency and purchasing power os over 18% each decade. As a result £1.00 today is worth £0.01 of a pound in 1945. Rather than emphasize productivity monetary policy and other policies attempt to avoid price declines (deflation) whereas this augments purchasing power and real incomes. |

|

|

At the same time managers need to take into account variations in unit prices of inputs which might cause changes in unit costs. Therefore the trade-offs that neeed to be considered include:

- changes in unit prices of inputs

- response in the setting of unit prices of outputs

- the resulting unit margins

- changes in volumes of output sold

- cash flow

Changes in the unit prices of inputs and outputs are normal and these are inflationary (increasing unit prices) or deflationary (falling unit prices). Inflation has a direct negative impact on real incomes as a result in a fall in the currency and disposable income purchasing power. Inflation has the effect of diminishing the full benefits of increasing productivity. Deflation is beneficial to currency and disposable income purchasing power but is ony sustainable if productivity is increasing.

One example of the change in unit output prices (UP) and unit margins (UM) that might occur as a result of changes in unit input costs (UC) is shown below in a simple 3x4 matrix containing different aspects of unit prices, unit costs and unit margins The green squares show the "starting point", the yellow squares show the change in absolute (d) and decimal percentage (%) terms and the blue squares show the outcome. This example shows that a rise of 10% in unit costs (rising from 60 to 66) is followed by a rise in unit prices of 10% (rising from 100 to 110) resulting in an increase in the unit margin of 10% (rising from 40 to 44).

| States | Initial | Transition | Final value | | Unit price data | UP | dUP | %UP | nUP | | 100 | 10 | 0.10 | 110 | | Unit margin data | UM | dUM | %UM | nUM | | 40 | 4 | 0.10 | 44 | | Unit costs data | UC | dUC | %UC | nUC | | 60 | 6 | 0.10 | 66 |

Key:

| UP: unit price; | dUP: absolute UP change; | %UP: percentage UP change; | nUP: is the net or final UP; | | UM: unit margin; | dUM: absolute UM change; | %UM: percentage UM change; | Net or final UM; | | UC: unit costs; | dUC: absolute UC change; | %UC: percentage UC change; | nUC: Net or final UC; | |

|

| States | Initial | Transition | Final value | | Unit price data | UP | dUP | %UP | nUP | | 100 | 10 | 0.10 | 110 | | Unit margin data | UM | dUM | %UM | nUM | | 40 | 4 | 0.10 | 44 | | Unit costs data | UC | dUC | %UC | nUC | | 60 | 6 | 0.10 | 66 |

Key:

| UP: unit price; | dUP: absolute UP change; | %UP: percentage UP change; | nUP: is the net or final UP; | | UM: unit margin; | dUM: absolute UM change; | %UM: percentage UM change; | Net or final UM; | | UC: unit costs; | dUC: absolute UC change; | %UC: percentage UC change; | nUC: Net or final UC; | |

|

In real incomes terms this situation has resulted in a net inflationary input of 10% result in a net output inflation of 10%. This, in terms of the purchasers of these goods and services, results in a 10% decline in the purchasing power of a given disposable income that would be dedicated to that product or service resulting in a fall in real income of that consumer. On the other hand the company has increased the margin by 10% against an increase in unit costs of 10%resulting in the purchasing powr of corporate funds spent on that input remaining the same and real income remaining constant. There is therefore, in this change in transactional conditions over the period concerned, a stability in the status of the corporate finance and a deterioriation in the consumer finances. There has not therefore been a Smithsonian impact of mutual benefit.

operation of the real incomes approach require precise data and a truthful compilation of that data. This is because companies not only manage their decisions but also the benefits that accrue from Price Performance Policy (PPP) are based on data reported by companies. However, experience shows that companies do resort to creative accounting so as to maximise advantages associated with accounting and statements of tax liability. The diffrence in the PPP environment is that there is no tax liablity and therefore this motivation for "manipulation" is absent.

In spite of that many managers see it as their function to push for advantage in any circumstances. In developing an economic policy that aims to achieve an effective distribution of economic growth throughout the economy there is a need to curtail some excesses of those who might with to pursue their objectives at the expense of others. This is a basic principle of constitutional economics. At the same time, correcting excesses should not place anyone at a disdavantage but simply ensure that abuse is effectively removed from the system.

For those who have followed the Real Incomes Approach it will be appreciated that a core data set is required to determine the contribution of any company to the status of the economy's real income. This data can be maintained in a block chain through which all transactions take place (purchases and sales).

Inflation

Thus under inflationary conditions the degree and direction in which a company influences price inflation is the Price Performance Ratio (PPR). The PPR can be measured as the ratio of the percentage increase in unit output prices to the percentage increase in total unit input values over a given period of time:

PPR = (100(dPo)/Po)/(100(dPi)/Pi)

PPR = (dPo .Pi)/(dPi.Po) ..... (1)

where:

dPo is the increase in unit output prices during the period and Po is the unit output price at the beginning of the period;

dPi is the increase in total input values per unit during the period and Pi is the unit input value at the beginning of the period.

This was the "original" formula I proposed for the PPR in 1976 that was designed to tackle inflation and this was published in the 1981 monograph.

Deflation

Thus under deflationary conditions the degree and direction in which a company influences prices can be measured as the ratio of the percentage fall in unit input costs to the percentage fall in unit output prices over a given period of time. Note that this is the inverse of the equation 1 above and it is therefore of the following form:

PPR = (100(dPi)/Pi)/(100(dPo)/Po)

PPR = (dPi .Po)/(dPo.Pi) ..... (2)

where:

dPo is the decrease in unit output prices during the period and Po is the unit output price at the beginning of the period;

dPi is the decrease in total input values per unit during the period and Pi is the unit input value at the beginning of the period. |

|

|

Some figures have been input to this table as an explanation of what it measures. The first column shows the state of unit costs, unit margins and unit prices at the beginning of a period. A product or service sold for £100 costs £60/unit to produce so each item sold generates a unit margin of £40. Over a given period, unit costs rise by £6 and unit prices are raised by £10 these raises are each equivalent to a 10% rise in costs and prices. The result is an increase in unit margin by £4 or £44/unit and increase in margins by 10%.

In real incomes terms the Price Performance Ratio (PPR) is:

(dUP/UP)/(dUC/UC) = %UP/%UC = 1.00

What has happened here is that an increase in unit costs has been met with an increase in unit prices by the same percentage rise as was witnessed in unit costs. The general rise in unit prices of 10% has been compensated by an increase in margin of 10% resulting. The Real margin, that is, the purchasing powr of the funds represented by the margin will depend upon the generat satte of price rises in the economy and in particular on the prices of importance to the operation of the company.

No matter what state the economy, it is possible for individual companies operating within a suitable policy framework to become generators of economic growth entirely based on supply side actions and without involving monetary policy interest rate fixing or variations on corporate taxation.

The Real Incomes Approach places the motor of innovation and growth in the hands of business and workforce management but providing incentives for efficiency arising from effective short term to medium term returns as opposed to the normal medium to long tern returns. Associated with this approach there is a need to lower corporate risk.

The ability of a company to generate short term returns depends upon the ability to sustain a growth in physical technological and/or price advantage in order to penetrate the market. The outcome of such growth in an increase in the purchasing power of the currency and general wellbeing of the population as a result. Typical examples are digital devices of all types that have been able to combine rising production efficiency with falling prices and increasing power of devices. In many other industries such impressive growth strategies are difficult to emulate but the recipe for succcess remains the same for all production and service sectors; there is a need for a form of productivity growth that benefits all.

The experience of the recent financial crisis and the behviour of the banks under quantitative easing are both examples of extra-constitutional arrangements for financial regulation failing the general population as a result of policy exacerbating the crisis of income concentration in the hands of fewer and fewer people. It is more than evident that low investment, declining productivity and real income levels and the growth in low income work and irregular employment requires that economic policies become more aligned with constitutional questions of fair treatment of, and opportunities for, all.

.

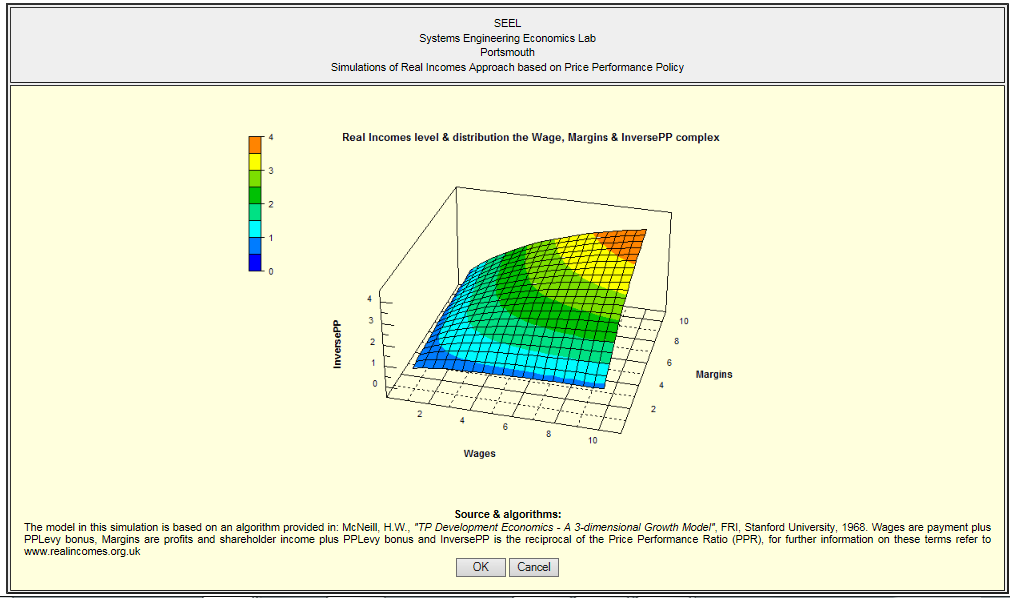

Just to review the interaction of changes in unit wages and corporate margins and in unit prices I used this old model to test PPP and the graphic output when limited to these three inputs (where unit price changes are the inverse (reciprocal) of the PPR). The potential outcome of this approach to supply side economics is a

better distrubution of a higher level of real income as shown in the simulaion of an early Real Incomes model below:

1 Hector McNeill is the director of SEEL-Systems Engineering Economics Lab.